Up until that point Blackwater had only trained a total 3,000 students in three years, but it won the contract, and would go on to train 20,000 sailors in six months, a feat the company is justifiably proud of. Plenty of well-financed ventures fail, though, and Blackwater was just a regional shooting school until the USS Cole was bombed in 2000 and the Navy determined it needed a new training program to teach sailors to guard ships in port. Whatever the motivation, the hardscrabble myth would be more compelling if we didn’t know he and his family had not just made $1.35 billion on the sale of his late father’s company. “Blackwater didn’t have some unlimited cash spigot to drink from,” Prince writes, but these challenges seem self-imposed, less financial reality and more a desire to his live up to his father’s example. The company scrimped and saved, and the wife of one manager helped out with the accounting books.

He was happy his first client (a SEAL team from California) paid the $25,000 bill with a credit card because they needed the cash flow. Prince invested $6 million of his own money to open the Blackwater campus in Moyock, North Carolina in 1998.

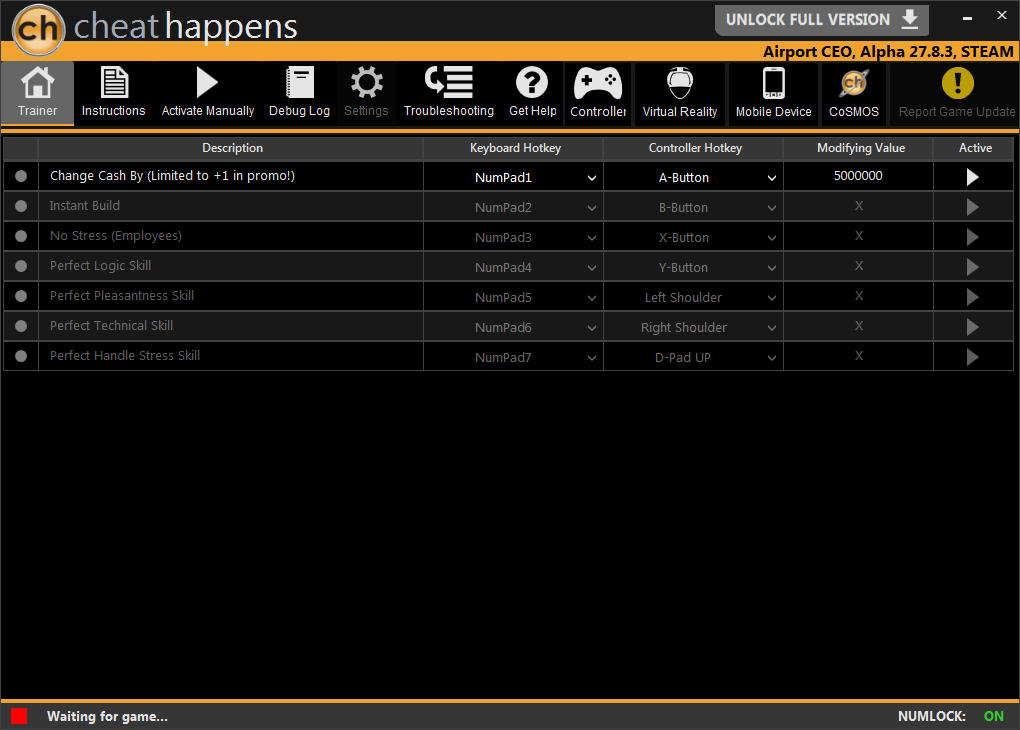

#Airport ceo more contractors cheat for free#

Blackwater airdropped supplies to stranded soldiers of the 82nd Airborne for free until the Air Force provided a contract. He rescues the US government when they cannot do a job for themselves. When he was thirteen he and his father rescued the passengers of a crippled boat on Lake Huron. His grandmother “sought no government handouts” when his grandfather died, his father started his multi-billion dollar company from scratch, his SEAL training class “had it even worse than many” but he persevered, he built Blackwater because of hard work and not inherited riches.īut most of all he is the great rescuer. He is a self-sufficient hard worker, and so is his family. He is a fighter and he wins, in combat or in the court room, even when he’s battling the families of his own slain employees. “I’ve watched that line in the sand shift far too much for it to act as any sort of standard,” he writes. A great beneficiary of the last three, to the tune of $2 billion, was Blackwater.ĭoes Prince find any functions inherently governmental? He thinks the distinction quaint. And while cities and counties kept police and fire departments sacrosanct and argued whether trash collectors were “inherently governmental,” the federal government quietly contracted out military food service then transportation then building maintenance then training then security then killing. Competent public administration is never sexy, and the NPR had a mixed and mostly forgotten record, but one piece of it has endured: the drive to privatize government functions.

It may be buried under layers of legal defense and rationalizing and being “done keeping quiet” and setting the record straight, but it is a worthy one, and a debate worth having, if Prince could get out of his own way.Īs a candidate twenty years ago, President Clinton made “reinventing government” part of his campaign platform, gave Vice-President Gore the task of making government more efficient via the National Performance Review. This is the fundamental question posed in the new memoir, Civilian Warriors, by Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater. Who should do the killing? Civilians or soldiers, government employees or private contractors? Does it even matter? Should it even matter? Does a decorated soldier become a villain when he performs the same actions in the same war as a contractor? Are some jobs, to use the standard idiom, “inherently governmental?”

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)